How Finca Maravilla is making wine in one of the driest places on the planet, Tacna Peru, is curious to be sure. Thanks to water running off the Andes via the Río Uchusuma, Tacna has some patches of green along the river’s edges, but not much else. It’s a huge gamble, and entirely reliant on that runoff. Some years are better than others, and everything is precarious due to climate change.

How Finca Maravilla is making wine in one of the driest places on the planet, Tacna Peru, is curious to be sure. Thanks to water running off the Andes via the Río Uchusuma, Tacna has some patches of green along the river’s edges, but not much else. It’s a huge gamble, and entirely reliant on that runoff. Some years are better than others, and everything is precarious due to climate change.

The Region

Finca Maravilla is, like most wineries in this region, first and foremost a pisco producer. As I wrote before, this is often a red flag. A great pisco maker does not reliably translate into a great winemaker; the grapes are different, as are the processes, equipment, and required terroir. But a lot of pisco producers figure they have enough of a toe in the water in “alcoholic beverage production” to wade from the pisco end of the pool into the winemaking end.

The Terrasur Red Blend is a blend of Cabernet Franc and Cabernet Sauvignon, blended with a primary element the label calls out as “Grenache-Syrah-Malbec.” This also hoists some red flags. First, why three of the grapes would be hyphenated together implies — but doesn’t outright state — this was something that was blended already, before having the cabs added. Next, it seems unlikely that Finca Maravilla has enough physical real estate in Tacna, much less the reliable weather and ground conditions, to grow plots of five grapes. Google Maps satellite view suggests they might, but the region is a vast, dead desert, with a rocky, sandy ground cover that makes planting anything a challenge.

So my spider-senses are telling me that this is a blend of wines produced elsewhere. But I’d probably be wrong. The Terrasur brand includes different offerings of standalone Cabernet Franc as well as Cabernet Sauvignon, and the marketing insists they’re made right there in Tacna. Ditto for a Terrasur Malbec. I’m still not sure where the Grenache and Syrah come from, though.

So my spider-senses are telling me that this is a blend of wines produced elsewhere. But I’d probably be wrong. The Terrasur brand includes different offerings of standalone Cabernet Franc as well as Cabernet Sauvignon, and the marketing insists they’re made right there in Tacna. Ditto for a Terrasur Malbec. I’m still not sure where the Grenache and Syrah come from, though.

So, until I physically visit them — which isn’t going to happen this year, at least — I have to keep wondering.

The Bottle

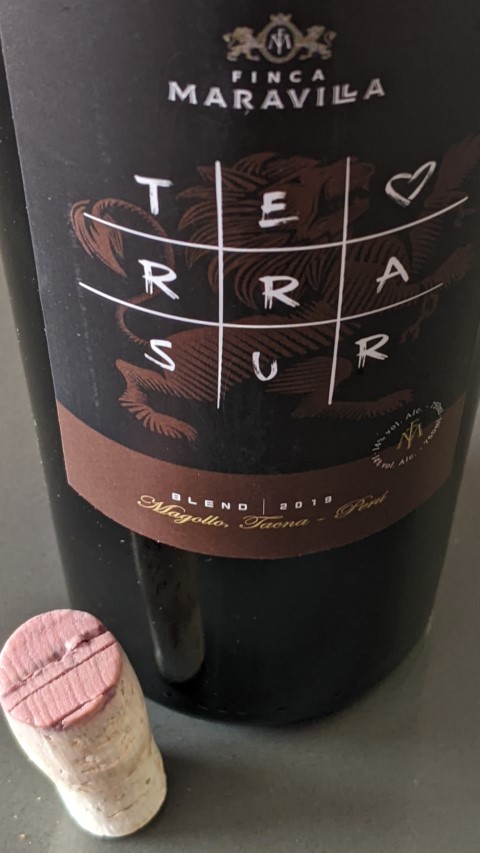

The bottle of Terrasur Red Blend arrived without incident, and showed promise. The bottle itself is black glass, hiding the contents but also protecting it from light. A black label was very well designed, but did show signs of peeling on one corner. Hmm.

I liked the Terrasur logo, a tic-tac-toe design that hides a cute secondary message. With each letter of “Terrasur” inserted into one of the available spaces, this left one space blank… so the designers added a heart symbol after the “T” and “E.” This is read as “te amo” in Spanish — meaning “I love you.” It’s cute, and well thought out.

Throughout the design is the lion imagery, which represents Finca Maravilla’s main crest logo. The name itself means “Wonder Estate,” if you’re interested. I think this lion branding adds a nice bit of regality to the entire brand, and shows some level of sophistication. As we will see in future reviews of Peruvian wines, “sophistication” is not a given.

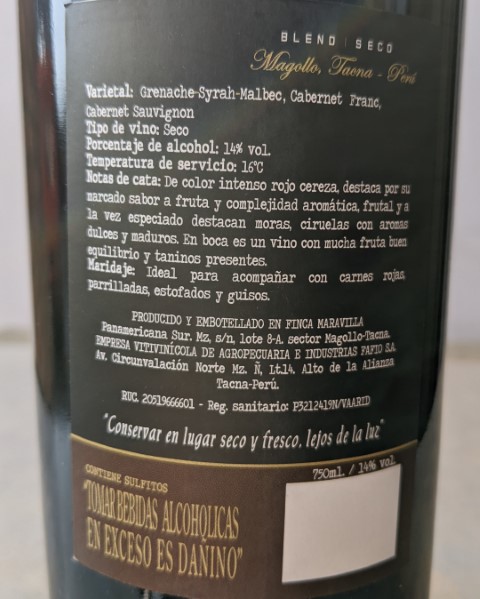

The back label provided a high level of detail, including a rough idea of the blend (although no details on actual percentages), tasting notes, etc. As I wrote previously, none of this is regulated under law yet, so clear information is always welcome on a Peruvian wine bottle.

The label insists, however, that the wine was bottled “en” Finca Maravilla — meaning on-premises, as I read it — as opposed to “por” Finca Maravilla, which would mean by them, and not at any actual location. So FM has gone all-in on insisting they’re bottling the stuff, and that it wasn’t a blend made by someone else, elsewhere in the country.

The label insists, however, that the wine was bottled “en” Finca Maravilla — meaning on-premises, as I read it — as opposed to “por” Finca Maravilla, which would mean by them, and not at any actual location. So FM has gone all-in on insisting they’re bottling the stuff, and that it wasn’t a blend made by someone else, elsewhere in the country.

The neck was properly sealed, which you must check with Peruvian wines. The foil was professionally attached, and pulled off normally. Again, some Peruvian bottlers haven’t mastered tasks we take for granted, like applying the neck seal, and some bottles aren’t sealed at all. The Terrasur bottle appeared no different than any normal wine from France or California in this respect, which was good news.

The cork, on the other hand, hinted at problems to come. Upon inspection, the cork looked natural — real cork, in other words, and not synthetic — but very pale and dry. This is common for Peruvian wines, since they often buy cheap cork from unreliable manufacturers. Such corks are rarely printed with any information, because the cork producers don’t want to spend money on stamping equipment. It’s common to find flimsy, bone-dry corks in cheaper, less professional wines in Peru, but this cork seemed to contrast against the highly professional presentation thus far.

Sure enough, it didn’t get better once the cork was pulled. It removed well enough (using a waiter’s key), but was so very dry, it gave off a slight cork powder in the process. The color of the underside threw up another immediate red flag; although perhaps calling it a “pink” flag would be better. The coloring was the palest pink I had seen since opening a rosé. The image below does the actual color justice; it was that pale. There was no marking on the cork, a sure sign of a cheap cork-maker.

This suggested the wine was stored upright, keeping the cork dry, and thus failing to protect the wine from air. A “wet” cork — soaked in wine that has been stored at an angle — expands the cork and tightens the seal. To store wine upright is a rookie error, and falls on both the producer (Finca Maravilla) and whatever distributor they are using. Since small Peruvian wineries may not even have a distributor, it’s likely that FM ships the stuff direct to the seller — in this case Peruvino — and it’s sold as-is. Peruvino rotates through its stock fast enought that it doesn’t do any long-term storage, so I’m putting the blame for this directly at Finca Maravilla.

Now remember that the vintage on this is 2019. It’s not an old wine by any stretch, but had the wine been stored properly, there’s no way this cork would be this color after nearly two full years.

The Pour

Pouring into a traditional red wine glass revealed no sediment, and a light purple color, nearly rusty. Tilting the glass revealed an amber middle, with not much opacity.

Despite a 14% level of alcohol, the legs on the wine were slight. There was very little adhesion to the glass.

The Nose

The nose immediately revealed “brett.” This is Brettanomyces, a yeast that can occur in some wines and has the potential to cause real damage. The resulting “brett” smell is that of horse or cow stable — in other words, shit — but in light amounts can actually enhance a wine. The level of brett tolerable by a person is highly individual, and the presence of brett isn’t always an indication that the wine is bad. For me, a little brett on the nose is fine, as it can enhance an earthy red.

Runaway brett, however, can cause disaster, especially when it follows through to the flavor profile. In 2017, the Winepisser Worst Wine award went to Franclin Delgado Castilla Cavas de Caral 2015 — from Peru, too, alas — because of overwhelming brett. I hadn’t known much about brett at the time, and didn’t realize that what I was tasting than even was brett. After having had the same experience a few times with Peruvian wines, I know now.

In the case of the Terrasur, my initial notes on nose were “horse stable” but also blueberry. So at this point, the brett wasn’t a deal-breaker.

Tasting

Now it was a deal-breaker. Tasting the wine proved the brett had carried through, and how. The stable flavors were now masking nearly everything about the wine, making it near impossible to even identify other notes. “Maybe some red berries?” I wrote in my notes. I was struggling.

I could make out some mouthfeel at least. Tannins were very smooth, and the acid was medium. The wine itself was super-dry, and pleasantly so. Had this thing not been tainted with brett, it might have been a good — although not great — red blend.

I knew brett doesn’t dissipate, but I gave the glass a second and third try out of pure desperation. For the second round, I let it sit for 15 minutes and revisited it. No change. I then poured a new glass through a Venturi, to try again. No change.

At this point, pairing with food wasn’t going to help, but I did my due diligence anyway. The plate was a simple hamburger and rice dish (hamburger served on the plate, not as a sandwich), and typically perfect for pairing with a red for taste-testing. No help here. After about a half-hour of trying, I gave up. It was undrinkable. The rest went down the drain — a clear sign of bad, bad wine.

Final score: 2.0 stars, giving the wine some extra credit for overall presentation, color, labeling and mouthfeel. I’m being, admittedly, generous.

Closing Notes

Other reviews on the Vivino app show the same exact vintage getting higher reviews, with no one mentioning brett or horse stable notes. A few drinkers actually enjoyed it. So whatever happened seems to have been unique to my bottle or, more likely, a few cases.

Brett really can’t happen from poor handling or storage after production, and must be introduced by the producer. So my thinking is that the batch has it uniformly, but the low-quality cork and upright storage gave this particular bottle the right conditions to allow the brett to grow wild. Perhaps other bottles were stored properly, and the brett never cultivated properly.

I’ll try another Finca Maravilla some day, sure. But for now, the first review of this Peru Wine Journey was a dismal disappointment.

For more entries in the Peruvian Wine Journey series, click here.